Gene Essentiality in budding yeast

Gene Essentiality in budding yeast¶

Essentiality of genes are defined as its deletion is detrimental to cell in the form that either the cell cannot grow anymore and dies, or the cell cannot give rise to offspring. Essentiality can be grouped in two categories, namely type I and type II [Chen et.al. 2016].

Type I essential genes are genes, when inhibited, show a loss-of-function that can only be rescued (or masked) when the lost function is recovered by a gain-of-function mechanism.

Typically these genes are important for some indispensable core function in the cell (e.g. Cdc42 in S. Cerevisiae that is type I essential for cell polarity).

Type II essential genes are the ones that look essential upon inhibition, but the effects of its inhibition can be rescued or masked by the deletion of (an)other gene(s).

These genes are therefore not actually essential, but when inhibiting the genes some toxic side effects are provoked that are deleterious for the cells.

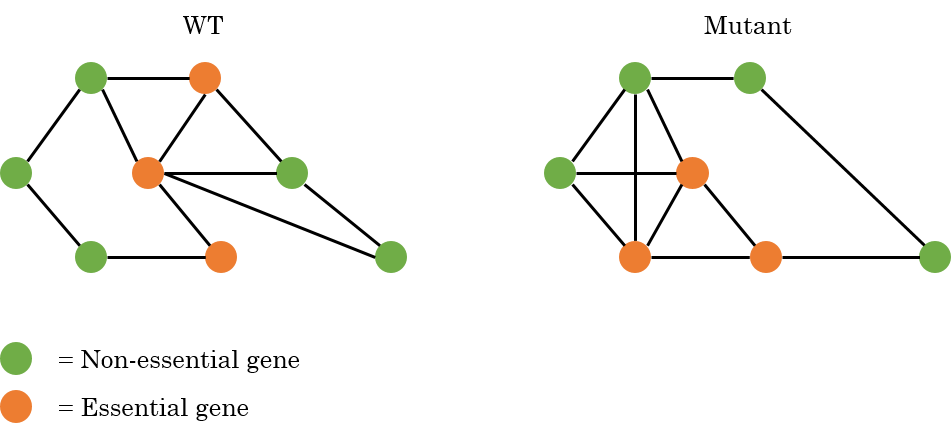

The idea is that the essentiality of genes (both type I and type II), may change between different genetic backgrounds. For changes in essentiality four cases are considered:

A gene is essential in WT and remains essential in the mutant.

A gene is non-essential in WT and remains non-essential in the mutant.

A gene is essential in WT and becomes non-essential in the mutant.

A gene is non-essential in WT and becomes essential in the mutant.

An example is given in the figure below, where an interaction map is shown for WT cells and a possible interaction map for a mutant where both the essentiality and the interactions are changed.

Situation 1 and 3 are expected to be the trickiest since those ones are difficult to validate. To check the synthetic lethality in cells, a double mutation needs to be made where one mutation makes the genetic background and the second mutation should confirm whether the second mutated gene is actually essential or not. This is typically made by sporulating the two mutants, but deleting a gene that is already essential in wild type prevents the cell from growing or dividing and can therefore not be sporulated with the mutant to create the double deletion. Therefore, these double mutants are hard or impossible to make.

Another point to be aware of is that some genes might be essential in specific growth conditions (see also the subsection). For example, cells that are grown in an environment that is rich of a specific nutrient, the gene(s) that are required for the digestion of this nutrient might be essential in this condition. The SATAY experiments will therefore show that these genes are intolerant for transposon insertions. However, when the cells are grown in another growth condition where mainly other nutrients are present, the same genes might now not be essential and therefore also be more tolerant to transposon insertions in that region. It is suggested to compare the results of experiments with cells from the same genetic background grown in different conditions with each other to rule out conditions specific results.

We want to check the essentiality of all genes in different mutants and compare this with both wild type cells and with each other. The goal is to make an overview of the changes in the essentiality of the genes and the interaction network between the proteins. With this we aim to eventually be able to predict the synthetic lethality of multiple mutations based on the interaction maps of the individual mutations.